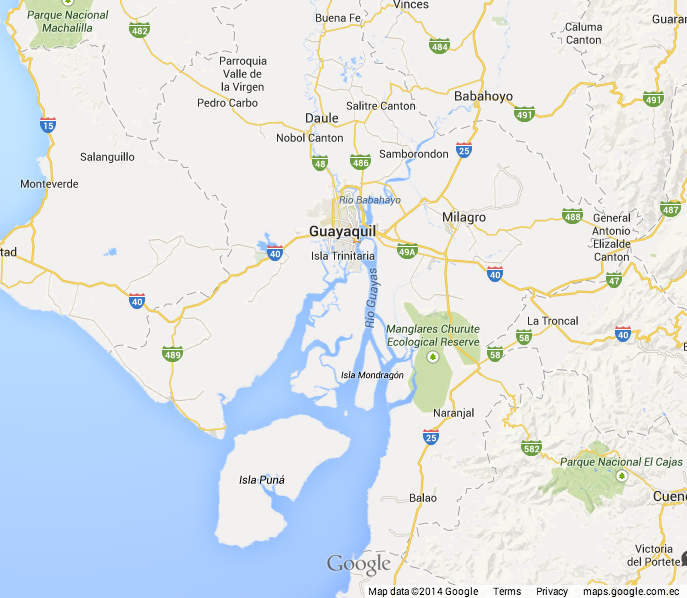

There are — at a coarse level — three Ecuadors. Guayaquil sits in a low part of a costal plain. Beyond the plain, the Andean highlands soar into the sky. The eastern slope of the Ecuadorian Andes gives way to the Amazon basin. My time in Ecuador regrettably affords me no opportunity to see thee the Amazon side.

|

| Ecuador consists of three principal geographic regions — a costal plain, the Andean highlands, and a corner of the Amazon basin. (Source: worldofmpas.net) |

My IBM CSC Ecuador team embarked on a weekend outing into the highlands. Cuenca — Ecuador's third city, after Guayaquil and Quito — was our primary destination. (I'll talk about Cuenca in a later installment.) We made two side trips. We stopped first at Ruinas Ingapirca, an important indigenous ruin. We also visited Cajas National Park. Radical changes in elevation was a key feature of our trip.

Our chartered bus allowed us to view en route a considerable amount of countryside. We began by transiting Ecuador's coastal plain. This relatively flat expanse bridges between the Pacific coast and the Andean foothills. The plain resides mostly below about 500 meters in elevation.

The coastal plain is home to much of Ecuador's agriculture. We saw vast expanses of banana plantations. These were interspersed with cocoa, rice, and a variety of other fruits. Ecuador presently enjoys robust growth in its agriculture output. Numerous new banana groves are evidence.

|

| Ecuador's coastal plane provides much of the country's banana production. |

Our introduction to the Andean foothills was obscured by cloud cover of the overcast morning. We witnessed a spectral unveiling as we climbed through about 1,500 m. The mountains gradually revealed themselves spectacularly. Once above 2,000 m, we enjoyed an unobstructed view of the peaks ahead of us.

The terrain almost could have been the Colorado Rockies of my youth. The mountainsides were rugged. We peered down into plunging canyons. The vegetation was however radically different. These plants of the equator know no changes in the season. They live in a perpetual Spring.

|

| The Andean foothills were masked by fog when we first climbed into them. |

We reached our first stop — the Ruinas Ingapirca — at around 3,100 m (10,000 ft) in elevation. This was a spiritually significant place for two pre-Colombian civilizations that chose to live at high elevations. The Cañaris occupied the site during about 500–1400 AD. They were supplanted by the Incas, who reined there until completion of the Spanish Conquest in about 1572 AD.

Las Ruinas Ingapirca demonstrate the Cañaris' surprisingly sophisticated grasp of astronomy. The geometry of the site is aligned to the sun's transit between its Summer and Winter solstices. The Cañaris — and their Incan successors at Ingapirca — were acutely aware of the celestial cycles.

Our tour guide, apparently of indigenous extraction, showed us a crude Cañari sextant. It consisted a large rock with holes into which water was poured. Its users observed stars' reflections in these little pools of water to divine the seasons and other things that mattered to them.

|

| The active period of the Ruinas Ingapirca spans both the Cañari and Incan periods in South America. |

Ingapirca compares modestly to the larger and more prominent Machu Picchu. It provides however a glimpse into Cañari culture. In this regard, it is distinctly Ecuadorian.

|

| Member's of IBM's Ecuador CSC Team examine the interior of a residence built to resemble those used by the Incans. |

We visited the following day one of Ecuador's natural wonders. Cajas National Park sits on the South American continental divide. This is the path along the top of the mountains that separates the continent into two drainages. Water on the West side ultimate drains into the Pacific. The East side drains into the Atlantic.

Cajas reminds me of Rocky Mountain National Park, near which I passed much of my youth. Both sit mostly above timber line. This is the altitude above which trees and other large plants can no longer survive. Timber line in the Colorado Rockies occurs at an altitude of about 10,000 ft (3,086 m). The visitors' center in Cajas sits at 13,539 ft (4,180 m).

|

| The Cajas National Park sits astride the South American continental divide. |

A diverse variety of other plants do survive in this rarified atmosphere. These include specially adapted grasses, lichens, and mosses. Their Colorado "cousins" are quite delicate. They grow slowly. These Andean plants may be slightly more robust, unconstrained by very short growing seasons.

|

| The flora in Cajas National Park consists of a variety of grasses, mosses, and lichens. |

My brief Andean visit elicited both nostalgia from a mountain childhood, and the excitement of a place that is new and exotic. Americans have a saying, "You can take the boy out of the mountains, but not the mountains out of the boy." There still are some mountains left in me. I find however that I am no longer adapted to higher altitudes.

The Andean environment is however very different however from the Colorado Rockies. The climate is severe enough to claim human lives. The site we visited — Las Tres Cruces — contains evidence in the form of three memorials. The Ecuadorian Andes, so near to the Equator, enjoy a perpetual Spring, by standards of the North American Rockies. That imbues them with a sense of strangeness and wonder.